What do osteoarthritis, obesity, type 2 diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, arteriosclerosis, asthma, and periodontitis have in common? Although genetic susceptibility may play a role in developing chronic, non-communicable conditions, they are primarily associated with lifestyle habits that trigger a subtle, pervasive change that changes the normal functioning of our systems, organs, and tissues: low-grade chronic inflammation.

The Good, the Not-So-Good, and the Bad: Acute Inflammation, Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation, and Pain

The Good

To be clear, inflammation is key to maintaining good health as a protective and adaptive response to trauma and infections (1). Let’s consider, for example, a muscle strain. A quick onset of redness, warmth, swelling, and pain are the main manifestations of acute inflammation; a normal response to tissue injury. When muscle fibers break down, they release chemotactic factors [e.g. interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)] that recruit circulating immune phagocytic cells (mainly monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils) to clear up the area of cellular debris and start off the repair process. Later on, a new wave of anti-inflammatory macrophages play a crucial role in muscle regeneration, by synthesizing collagen and directly promoting myogenesis by releasing growth factors that stimulate the division of muscle stem (satellite) cells (2).

The Not-So-Good

Neutrophils, however, can be overzealous. This class of leukocytes will ‘assume’ that there is already an infection (a severe threat during open traumas), and go on to release free reactive oxygen species (i.e. hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, hypochlorite) with potent antibacterial activities. During low-grade chronic muscle inflammation, neutrophils will become overactive and release a lot more free radicals. The problem is, the toxicity of these ‘free radicals’ is not specific, so in addition to killing any bacteria that may be present (which is clearly a good thing), they may oxidize and damage tissue proteins, DNA, and lipids, thus lengthening recovery and perpetuating pain. This is the reason that applying ice and restricting blood flow to the affected area are recommended to reduce inflammation after a muscle strain (3, 4).

The Bad

Though pro-inflammatory changes occur after tissue damage to signal immune cells of potential danger and to facilitate repair, lack of resolution to inflammatory status renders the condition chronic, and perpetuates pain. It turns out that continued inflammation is, in many cases, due to poor nutritional habits and physical inactivity (5, 6). Together, these things contribute to low-grade chronic inflammation; a state of altered cell metabolism and unbalanced immune reactivity that can be systemic or that can affect specific organs or tissues. A key component of this condition is oxidative stress, namely due to excessive production of free radicals over antioxidants. Though free radicals are critical, antibacterial byproducts of cellular respiration, they are also powerful cellular aggressors. Low-grade chronic inflammation is instigated and aggravated by poor nutrition, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, air pollution, hazardous chemicals and pesticides, and is frequently associated with subclinical endotoxemia (i.e. low levels of LPS/endotoxin, the main infective agent of bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Pseudomonas, and Neisseria). Thus, although self-resolving inflammation and low-level free radical production are normal events during immune response and cellular function, they may lead to persistent health problems and pain if disrupted (7).

To better appreciate how lifestyle choices contribute to low-grade chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, let’s investigate three main culprits:

Hyperglycemia

Glucose is slowly produced by digestion of complex carbohydrates, but quickly released from refined sugars like table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup. It is the main fuel used by mitochondria for energy (ATP) production during cellular respiration. When plasma glucose levels rise (i.e. high blood sugar or hyperglycemia), mitochondria go overboard and produce supra-physiological levels of free radicals in the cell. In turn, this increases calcium entry into cells, disrupting signaling pathways, membrane transport mechanisms, and leading even to cell death (8). Persistent hyperglycemia eventually causes insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome (prediabetes), and diabetes mellitus. Research has shown that hyperglycemia also contributes to widespread (systemic) low-grade chronic inflammation, by increasing circulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as Interleukins 6 and 18 (IL-6, IL-18), and TNF-α (9). Last but not least, excess sugar makes us overweight, as it is converted to fat in the liver, and stored in our adipocytes.

Hyperlipidemia

Excess dietary fat is stored in adipose depots throughout the body. When adipocytes become too large, two unsavory things happen (primarily in visceral fat depots): 1) They become a vast source of pro-inflammatory adipokines (adipocytes cytokines); and 2) They break down triglyceride and start leaking non-esterified fatty acids (FFAs) into the bloodstream. If not metabolized promptly, FFAs may accumulate, forming plaque within arterial walls and the liver (leading to hepatic steatosis, or “fatty liver”). Excess FFAs contribute to insulin resistance by inhibiting glucose uptake in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and the liver, also disrupting insulin production in the pancreas. They also promote free radical production by neutrophil and macrophages, increasing the load and peripheral delivery of pro-inflammatory chemokines by red blood cells. Interestingly, saturated fatty acids share structural and functional properties with bacterial endotoxin, and both can trigger the expression of common proinflammatory genes (10, 11, 12). Of course, not all fats are created equal; here is a look at which ones will actually help in reducing inflammation and pain.

Smoking

Tobacco smoke contains more than 4000 chemicals, of which at least 250 are known to be harmful and more than 50 are known to cause cancer (13). The irritants in tobacco smoke are key contributors to low-grade systemic chronic inflammation because they damage the vascular endothelium (the thin layer made up of single cells that lines blood vessels), potentially affecting every single organ in the body. It is said that the endothelium becomes reactive, or more ‘sticky’, which allows the activation and infiltration of immune cells into tissues. An inflamed endothelium also shows impaired coagulatory capacity, meaning it becomes pro-thrombotic, leading sometimes to hypertension through the decreased production of its main vasodilatory substance, nitric oxide (NO) (14).

Sedentary Time

Sedentary behavior influences markers associated with inflammation, that are often independent of one’s physical activity level, glycemic health and weight. Time spent sitting and not moving has been positively associated with elevated CRP levels and elevated adipokines (IL-6, leptin, and LAR) even after controlling for various confounding variables. Daily exercise in the gym for 30-minutes may no longer be the best recommendation. Movement is medicine, little doses throughout the day to interrupt the habit of sitting and other sedentary behaviors are recommended for optimal health, and to prevent risk factors associated with chronic disease and chronic pain.

Tobacco smoke contains more than 4000 chemicals, of which at least 250 are known to be harmful and more than 50 are known to cause cancer Click To TweetVirtually every chronic condition and disability without a defined genetic component, from diabetes to osteoarthritis to heart disease, has its roots in low-grade chronic inflammation. Caused by poor nutrition habits and sedentarism, inflammation is often compounded by stress, trauma, smoking, and environmental pollution. It is likely that inflammatory conditions such as these are prevalent because develop slowly, over the course of years, due to repeated stress. Most of the time we are oblivious to the physiologic changes in our muscles, blood vessels, liver, and lungs, until the pain begins.

Fighting Back, Naturally: Healthy Diet and Physical Activity Prescription to Reverse Low-grade Chronic Inflammation

Though anti-inflammatory medications are commonly prescribed to ease the symptoms of inflammation and pain in osteoarthritis, diabetes, and other chronic diseases, they do not treat the underlying causes, and sometimes they cause severe side-effects (15). A research article by Elizabeth Dean, PT, Ph.D. and Rasmus Gormsen Hansen, PT, Ph.D. makes the excellent point to prescribe optimal nutrition and physical activity as a “first-line” intervention for low-grade inflammation associated with chronic osteoarthritis, and other lifestyle-related conditions (16).

The main arguments can be summarized as follows:

-

- Extensive research supports that the western diet (high in saturated fats and refined sugars) and an inactive lifestyle are proinflammatory, while a plant-based diet and regular physical activity are anti-inflammatory

-

- Low-grade inflammation is common across lifestyle-related conditions including osteoarthritis

-

- Best practice guidelines for chronic osteoarthritis focus on self-management, or weight control and physical activity, with pharmacological support for inflammation and pain

- Evidence-based recommendations for lifestyle behavior change that can be readily integrated by health practitioners into cost-effective, “first-line” management.

Having reviewed the evidence supporting the anti-inflammatory diet and how the Mediterranean diet mitigates osteoarthritic pain, let’s take a look at the two main anti-inflammatory benefits of physical activity:

- Weight loss and control: Exercise promotes weight loss by boosting metabolism (burning fat reserves) to provide the extra energy required, and by stimulating the production of catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) that trigger lipolysis (lipid breakdown) in adipocytes (17, 18). Losing weight reduces the burden of hyperlipidemia, calms its proinflammatory effects, and restores insulin sensitivity.

- Resolution of inflammatory responses: Moderate exercise (like fast walking) triggers the release of small amounts of IL-6 and catecholamines. By respectively acting on a distinct IL-6 receptor complex (via classic-signaling) and on β2 adrenergic receptors present on monocytes/macrophages, these molecules inhibit TNF-α production, stimulate anti-inflammatory IL-10 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), and shift the activity of these cells towards an anti-inflammatory status(19, 20, 21).

- Lower stress, restful sleep: Both physical and psychosocial stress, and sleep deprivation result in metabolic imbalances that facilitate and potentiate inflammation (22). By reducing stress and improving sleep quality, regular physical activity indirectly helps to lower inflammation and alleviate pain.

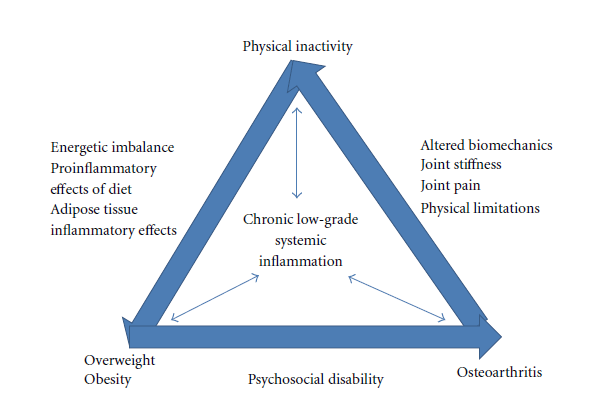

The figure below summarizes the relationship between osteoarthritis, obesity, and physical inactivity and how they relate to the etiology of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation (Reprinted from (16)).

Image from: E. Dean and R. Gormsen Hansen, “Prescribing Optimal Nutrition and Physical Activity as “First-Line” Interventions for Best Practice Management of Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation Associated with Osteoarthritis: Evidence Synthesis,” Arthritis, vol. 2012, Article ID 560634, 28 pages, 2012

By reducing stress and improving sleep quality, regular physical activity indirectly helps to lower inflammation and alleviate pain. Click To TweetDr. Tatta’s simple and effective pain assessment tools. Quickly and easily assess pain so you can develop actionable solutions in less time.

Tackling Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation and Pain: A Physical Therapist’s Role

Drs. Dean and Hanson’s article emphasize that effective promotion of lifestyle changes in patients with conditions associated with chronic low-grade inflammation would require a concerted efforts by physicians, nurses, and physical therapists:

Consistent with 21st-century epidemiological trends, physical therapists are moving toward a model of care based on health (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health) which includes initiating and supporting behavior change such as optimal nutrition, weight reduction, reduced sedentary activity, and increased physical activity.” (16, 23)

Learning how low-grade chronic inflammation causes chronic diseases, disabilities, and pain, and acquiring the skills needed for effective counseling on health and wellness habits will allow physical therapists to become main players in the prevention and management of chronic pain.

What are your thoughts? Please leave us a comment below, and visit us on Facebook!

REFERENCES:

1- Scott, A., Khan, K. M., Roberts, C. R., Cook, J. L., & Duronio, V. (2004). What do we mean by the term “inflammation”? A contemporary basic science update for sports medicine. British journal of sports medicine, 38(3), 372-380.

2- Yang, W., & Hu, P. (2018). Skeletal muscle regeneration is modulated by inflammation. Journal of orthopaedic translation.

3- Toumi, H., F’guyer, S., & Best, T. M. (2006). The role of neutrophils in injury and repair following muscle stretch. Journal of Anatomy, 208(4), 459–470.

4- Pizza, F. X., Peterson, J. M., Baas, J. H., & Koh, T. J. (2005). Neutrophils contribute to muscle injury and impair its resolution after lengthening contractions in mice. The Journal of physiology, 562(3), 899-913.

5- Minihane, A. M., Vinoy, S., Russell, W. R., Baka, A., Roche, H. M., Tuohy, K. M., … Calder, P. C. (2015). Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. The British Journal of Nutrition, 114(7), 999–1012.

6- Wärnberg, J., Cunningham, K., Romeo, J., & Marcos, A. (2010). Physical activity, exercise and low-grade systemic inflammation. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 69(3), 400-406. doi:10.1017/S0029665110001928

7- Inanır, A., Sogut, E., Ayan, M., & Inanır, S. (2013). Evaluation of Pain Intensity and Oxidative Stress Levels in Patients with Inflammatory and Non-Inflammatory Back Pain. European Journal of General Medicine, 10(4).

8- Görlach, A., Bertram, K., Hudecova, S., & Krizanova, O. (2015). Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biology, 6, 260–271.

9- Esposito, K., Nappo, F., Marfella, R., Giugliano, G., Giugliano, F., Ciotola, M., … & Giugliano, D. (2002). Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation, 106(16), 2067-2072.

10- Gregor, M. F., & Hotamisligil, G. S. (2011). Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annual review of immunology, 29, 415-445.

11- Unruh, D., Srinivasan, R., Benson, T., Haigh, S., Coyle, D., Batra, N., … & Franco, R. S. (2015). Red blood cell dysfunction induced by high-fat diet: potential implications for obesity-related atherosclerosis. Circulation, 132(20), 1898-1908.

12- Fritsche, K. L. (2015). The Science of Fatty Acids and Inflammation. Advances in Nutrition, 6(3), 293S–301S.

13- World Health Organization – Tobacco http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

14- Messner, B., & Bernhard, D. (2014). Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 34(3), 509-515.

15- Barr, A., & Conaghan, P. G. (2012). Osteoarthritis: a holistic approach. Clinical Medicine, 12(2), 153-155.

16- Dean, E., & Gormsen Hansen, R. (2012). Prescribing Optimal Nutrition and Physical Activity as “First-Line” Interventions for Best Practice Management of Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation Associated with Osteoarthritis: Evidence Synthesis. Arthritis, 2012, 560634. http://doi.org/10.1155/2012/560634

17- Zouhal, H., Lemoine-Morel, S., Mathieu, M. E., Casazza, G. A., & Jabbour, G. (2013). Catecholamines and obesity: effects of exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 43(7), 591-600.

18- Wiklund, P. (2016). The role of physical activity and exercise in obesity and weight management: Time for critical appraisal. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 5(2), 151-154.

19- Fuster, J. J., & Walsh, K. (2014). The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of interleukin-6 signaling. The EMBO Journal, 33(13), 1425–1427.

20- Dimitrov, S., Hulteng, E., & Hong, S. (2017). Inflammation and exercise: Inhibition of monocytic intracellular TNF production by acute exercise via β2-adrenergic activation. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 61, 60-68.

21- Gleeson, M., Bishop, N. C., Stensel, D. J., Lindley, M. R., Mastana, S. S., & Nimmo, M. A. (2011). The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nature Reviews Immunology, 11(9), 607.

22- Lacourt, T. E., Vichaya, E. G., Chiu, G. S., Dantzer, R., & Heijnen, C. J. (2018). The High Costs of Low-Grade Inflammation: Persistent Fatigue as a Consequence of Reduced Cellular-Energy Availability and Non-adaptive Energy Expenditure. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 12.

23- Dean, E. (2009). Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part II): Evidence-based practice within the context of evidence-informed practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 25(5-6), 354-368.